A pioneering, visionary, controversial, prolific, influential, multi-skilled and passionate man, reconciling the twofold nature of photography as both a commercial and artistic artwork, a tireless experimental artist, still too little known, Edward Steichen went through the most challenging events of his time. He participated from inside to the most crucial moments of the 20th century in History as well as Art, but above all he was a visionary witness who never stopped trying to praise the richness of the world and its multidimensionality.

Edward Steichen, Self-Portrait with Studio Camera, 1917 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

1879- 1894: Coming into the world in the heart of the world

Edouard Jean Steichen was born on 27th March, 1879 in Bivange, Luxembourg. He was barely 2 years old when his parents moved to the United States, in the continuity of the great European migrations, driven by the hope of a more prosperous life in a country across the ocean. For young Edouard it would be the first of a long series of back and forth trips between the old continent and the young one.

In the United States, the family settled in Hancock, Michigan and life got smoothly organised. First a new child was born, Lilian. Then Eduard’s mother started a small hat business. Very determined, pragmatic and open-minded she managed the finances of the family and became committed to the cause of women, more especially the women’s right to vote.

Edward Steichen, Jean-Pierre Steichen, Bequest of Edward Steichen/Collection MNHA Luxembourg © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Steichen, Mary Steichen, Bequest of Edward Steichen/Collection MNHA Luxembourg © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Steichen, Self-Portrait with Sister, 1899, Bequest of Edward Steichen/Collection MNHA Luxembourg © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

His father was a dreamer. He was working in a copper mine, was in poor health and he preferred to devote himself to his garden, sharing with his children his passion for plants. Edouard began attending Pio Nono College, a Catholic boys’ high school, where he quickly got bored accepting with reluctance to follow the rules. He soon became noted because of the jokes he was never short of and his aptitude for art.

The child before the artist

The greatest artists are not always the wisest… In fact, it is even the opposite! And Edouard, as a child, was no exception to the rule. His family nicknamed him “Gaesjack” (an old Luxemburgish expression) or “Gaassejong” which means urchin. He was so mischievous!

His teachers, as well as his mother, encouraged him to hone his skills as a painter and a drawer. He developed a passionate interest for those activities, and even sometimes gave a little personal boost to his creativity.

A kind of artistic cheating

In his autobiography, Steichen confessed that one day, as he had been asked by a teacher to draw tulips, he had traced the drawings of flowers from a botany book and then wiped off the traces of the contours.

1895-1899: First experiences, both in painting and in photography

At age 15 he left school and began an apprenticeship at the American Fine Art Company in order to become a lithographer. Very soon his employer noticed his artistic talent and creativity. He helped him to discover graphic design, giving the opportunity to win his first award for having designed an envelope. The young Steichen began then to create posters and other graphic supports, even for his mother’s small hat business. For the first time he had to deal with the relationship between word and image, art and context.

Lithography

Lithography is a printing process of producing a picture, writing, or the like, on a flat limestone with some greasy or oily substance.

Laxatives

Edouard created for the laxative Cascarets, an amazing advertising poster: it was composed of one element from The Birth of Venus, a famous painting from the 19th century by Alexandre Cabanel with the slogan “They (the laxatives) work while you sleep”. With his so characteristic arrogance, Steichen broke the taboo on a delicate subject. Two years later, this ad was displayed on a height of a 6 storey-building and over a width of a block of flats in New York.

Edward Steichen, Advertisement, American Fine Art Company, 1899

Edward Steichen, My Little Sister, 1895 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Steichen, Portrait Study, 1898 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While getting involved in paintwork, he tried photography but was particularly disappointed by his first shots. Indeed, he bought a second-hand Kodak box camera and started to photograph everything in his home using the whole film. But when he developed it, only one picture was worth printing: it would be his first photograph named My Little Sister, a portrait of Lilian sitting at her piano. He was only 16 and, from that moment on, Eduard would never stop experimenting, both through painting or photographs, concentrating first on natural representations of his environment and his entourage.

When he was 18 the aspiring artist realised a self-portrait ‘Portrait Study’ awarded at Philadelphia Salon. And yet the picture was controversial in the world of photography since the perspective, the framing and the composition were unusual for the time.

The definition of photography

What is photography? From the Greek phôs, phôtós (“light”) and gráphô (“writing”), photography literally means “writing with light”. Invented in 1826 by Joseph Niépce, at the crossroads of optics and chemistry, it refers to a technical process enabling an image to be fixed on a photosensitive surface thanks to light. Since its discovery, it has evolved steadily, with the successive invention of negatives, flexible images, colour photography, film, instant photography, 3D pictures, digital photography, computer images, astronomy photography. And it is not yet finished. Nowadays we can distinguish analogue photography and digital photography. The principle remains the same: the basic idea is to capture and fix the light that each object reflects (exactly what happens in our eyes when we look at it). It is just the manner that differs. The first process implies light action when it enters through the shutter and reflects on a light sensitive photographic film, which will have to be bathed in a liquid chemical solution to reveal the image. It is named development or processing. For digital photography the film is replaced by electronic photodetectors which transform the light into an electrical signal, creating thus pixels that will gather to create an image.

1900-1902: Marking the turn of the century and leaving his mark, a foot in both worlds.

In the early 19th century, for his 21st birthday, Edouard Steichen became a US citizen under the name Edward Steichen. In the same year, at a moment when his exhibitions were becoming more and more successful at Philadelphia Salon, Chicago Salon or in private circles..., he set sail with his best friend for a bicycle ride through Europe. It was the beginning of a new life for Steichen between Europe and the United States, enriched by encounters, events or inspirations.

Once settled in Paris, Steichen met Rodin. Between artistic collaboration and sincere friendship, their interest is immediately mutual. Later Steichen was to name his daughter Kate Rodina as a tribute to Rodin when he became her godfather. The photographer was much impressed by the sculptor’s use of material and this last one was fascinated by a man who could freeze a moment while letting his imagination and creativity run free. For one year Steichen did a series of portraits as well as photos of his sculptures.

Carl Björncrantz, Edward Steichen on a bike

Edward Steichen, Rodin—The Thinker, 1902 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Steichen enrolled at the Académie Julian to learn painting but quickly abandoned studies that he thought too academic. Well integrated in the cultural, artistic and intellectual circles of the pre-war swirling Paris, he photographed several personalities like Anatole France, Richard Strauss or Henri Matisse.

Paris, salon du Champ-de-Mars

For the Parisian salon du Champ de Mars, dedicated to artwork, Steichen sent highly retouched photos that he presented like pictorial creations. The jury, only composed of painters, enthusiastically accepted the propositions. At the last minute they realised that everything was fake and none of the work was exposed. As for Steichen, he was embroiled in a controversy widely relayed by the international media which questioned the photograph as a part of the fine arts. This matter earned him the nickname of “terrible child of photography”.

1903-1922: Between the United States and France, inspirations and experimentations

In 1902, as his first individual exhibition of both paintings and photographs was in full swing in Paris, Steichen decided to go back to New York. There he married Clara Smith, a dancer with whom he was to have two girls and he opened his own portrait photography studio. Invited by Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer and publisher of the journal Camera Work, Steichen joined the Pictorialist movement Photo Secession aimed at promoting photography as a modern art. Thus, in a pictorialist self-portrait, Steichen considered himself a painter even though photography was the chosen medium.

Pictorialism

The style known as Pictorialism represented both a photographic aestheticism and the international artistic movement that followed. This movement was commited to getting photography recognized as an art and not reduced to the mechanical reproduction of a given reality. The Pictorialists manipulated the aesthetics of images in a painterly manner and laboured in the darkroom to touch up photographs in order to give them an artistic touch. For instance, blurring a photo could appear like a “sign of recognition” for creativity, as opposed to photo’s sharpness that was purely due to a machine.

Edward Steichen, Brooklyn Bridge, 1903 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Cover designed by Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen, Le Tournesol (1920) © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Steichen, Self-Portrait with Brush and Palette, 1903 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1905 Steichen and Stieglitz opened together the modern art gallery The little Galleries of the Photo-Secession or Gallery 291. Indeed, it was situated 291, Fifth Avenue in New York, at the exact place where Steichen’s old studio was. Steichen influenced Stieglitz’s choice of the artists that should be exhibited and transformed himself in an ambassador of the “French connection” and invited many artists of all stripes to exhibit their work: Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Brâncuși…

I believe that art is cosmopolitan and that one should touch all points. I hate specialism. That is the ruin of art.

Edward Steichen

In the following years Steichen shared his time between Paris and New York and undertook an intensive photographic work. With his pioneering and versatile spirit, trying everything, curious about every subject and more passionate than ever Steichen blossomed in his art, exploring numerous techniques, for instance experimenting the Autochrome process and expanded in all areas of photography.

One of the most expensive photographs of the world

The photograph entitled The Pond-Moonlight is a view of a pond in the woods under the moonlight. The moon shines between the trees and is reflected in the pond. Even if the first colour photography process the Autochrome was not used before 1907, Steichen managed to create a coloured impression using light-sensitive gums that he manually applied. In 1904 when he took this photograph very few photographers had dared using this experimental technique. Only three versions of the photo are known - two of them being held in museum collections - and because of the hand-layering of gums each of them is unique. In 2006, a print of the photograph was sold for $2.9 million at Sotheby’s making it the most expensive photograph sold at auction.

Edward Steichen, Moonrise—Mamaroneck, New York, 1904 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

He photographed portraits of famous persons like JP Morgan that came to be known as a classical work among photographic portraits, politicians from the socialist party that he joined following his sister and mother, or the American president Theodore Roosevelt…

The case JP Morgan

When Steichen was asked to realise JP Morgan’s portrait, he had planned everything except the mood of his model. Before the shoot he had perfected the position and the lighting by having a janitor sit in Morgan’s place, in order to shorten the exposure time for the finance tycoon. For the second shot his request slightly annoyed JP Morgan who took a somewhat aggressive expression. Besides, the light focused on the arm of the chair gave the illusion of a dagger. JP Morgan tore up the second proof, making Steichen realise that the photo might have some value. He made a new bigger print and gave it to Stieglitz to be displayed as a “masterpiece of the pictorialist photography”. When JP Morgan discovered that his portrait had been made a masterpiece, he wanted to own it. However, Steichen procrastinated for some years before he accepted to sell him a copy.

Edward Steichen, J.Pierpont Morgan, 1903, Bequest of Edward Steichen/Collection MNHA Luxembourg © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Creation of a children’s book

In 1930, Edward Steichen realized a book for babies conceived by his eldest daughter, Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone. Working together as a team, Steichen and his daughter used toys, clothing, and other items taken from her own household when her two little girls were very young.

The First Picture Book: Everyday Things for Babies intentionally has no text, and shows twenty-four black and white photographs of everyday objects: a teddy bear, a ball, a wooden train, a crib, shoes and socks, taken as studio close-ups under artificial light. The illustrations are objective and free of emotion, almost scientific. The aim is to show specific childhood objects that are critical and necessary elements in the early life of a small child.

Far from a simple picture book, this work from the 1920's also asserts a certain vision of progressive education that aimed to encourage children to learn to identify in their own words the everyday items around them. It was the first children's book published that used photographs and not illustrations, and the lack of text was done intentionally so that children could describe the photographs themselves without intermediaries, and thus begin to make direct connections between themselves and the things around them that were a part of their everyday lives.

The Second Picture Book that followed the publication of the first, moved children past the immediacy of their infant surroundings and put them into photographs with some of the items from the First Picture Book and, thus, out into the world.

Edward Steichen, Shoes and Socks - The First Picture Book, 1930 Bequets of Edward Steichen/Collection MNHA Luxembourg © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Steichen also turned to experimental photography of objects and shapes. He got passionate for pictures of insects, flowers and plants and in 1908 he rented a farmhouse in Voulangis, near Paris. He devoted himself to horticultural experiences and created for the first time hybrids of delphiniums that granted him famous awards from the botanical world: a gold medal in Paris and a prize for the best potato crop (Seine-et-Marne).

Edward Steichen, Lotus, Mt. Kisco, New York, 1915 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Dana Steichen, Edward Steichen with delphiniums, c.1938, Umpawaug House (Redding, Connecticut) © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Steichen, Delphiniums, 1940 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Growing plants made me learn more about people and nature than you might think.

Edward Steichen

When the First World War broke out, he went back to the United States and was commissioned first lieutenant of the photographic division of the Army Expeditionary Forces, devoting much of his work there to aerial photography over France. The end of the conflict left him emotionally afflicted and distraught, full of bitterness, which meant the end of his first marriage. He had grown disillusioned and he burnt his paintings in the garden of his home in Voulangis. He decided to devote himself entirely to photography, rejected Pictorialism and was to revert to the “straight photography”. This is a real turning point in his career.

Straight photography

Although existing before World War I, this artistic movement took on its full meaning and became quite popular among photographers like Stieglitz or Paul Strand during the world conflict. In contrast to Pictorialism, “straight photography” referred to the picture as it is, without any artifice nor rework when it came to printing. Reality was thus sharply captured only through the camera lenses and the photographer’s eye which could reveal its structure, its light and its shapes to have a unique composition. Thanks to more sensitive films and lighter equipment, photography gained popularity and began to reflect the reality of the world, but also to show it in a more graphical and aesthetic, sometimes even abstract way.

Edward Steichen, Milk Bottles: Spring, New York (1915) © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Unknown photographer, Captain Edward Steichen and Camera, Serving with the American Expeditionary Forces in France, 1918. Helga Sandburg Crile Collection

Edward Steichen, Untitled (Vaux), 1918/19 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

1923-1938: The Capitalist consumer society as a support for social struggles

In 1923 for his 44th birthday, Steichen remarried to actress Dana Desboro Glover and the couple settled permanently in New York. From 1923 to 1938, he worked for the Condé Nast publications as the chief photographer. He raised the standards of fashion and commercial photography taking portraits of famous people or film stars like Greta Garbo, and had his photos published in Vogue whose first colored cover page he would realise in 1932. He also worked for Vanity Fair and was to become the highest paid photographer of his generation.

Edward Steichen, Greta Garbo (for Vogue), 1928 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Edward Steichen, Actor Paul Robeson in costume for Eugene O'Neill's "The Emperor Jones," and looking over the collar of his millitary jacket, Vanity Fair 1933, Condé Nast © Getty Images

Celebrity didn’t make him abandon his convictions. Together with the portraits of famous African-American people that he had made in the 1920s, he published for the first time a portrait on a page by the American artist Florence Mills for Vanity Fair in 1924. He also realised a portrait of Paul Robeson, the first African-American actor to play a starring role in an American film in 1933.

An historic trial: Brânçusi vs United States

In 1926, Steichen bought Brânçusi’s sculpture Bird in Space.

When he brought it back to the United States in order to exhibit it at Gallery 291, New York Customs refused to declare it as a piece of artwork and asked Steichen to pay a tax of about $600. They advocated that it was a banal cooking utensil. This case was to go to trial and the court would have to define what a piece of art was and what it was meant to resemble.

Edward Steichen, Brancusi's Studio, 1920 © 2021 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

He purchased a house in Redding, Co, where he definitely settled in 1938. He left Condé Nast and devoted himself to his passion for botany. He went back to his old love for delphiniums and harnessed his passion so far as to organise in 1936 an exhibition at the MoMA. Plants that Steichen had raised himself were shown for one week only. Between 1935 and 1939 he even became the president of the American Delphinium Society.

This is Edward Steichen television special produced by WCBS-TV, originally broadcast April 12, 1965. American photographer, Edward Steichen at his property, Umpawaug, in Redding, Connecticut. Shown here with his Irish Wolfhound, Finn Tan. Image dated March 25, 1965. (Photo by CBS via Getty Images)

1938-1947: When engagement becomes art

Far from the conception of an art disconnected from reality, from the challenges or major questions facing society of his time, Steichen militated for causes such as racism, anti-Semitism, fascism and social inequalities that had been nurturing his photographic work and his relationships with others.

Art for art’s sake is dead, if it ever lived.

Edward Steichen

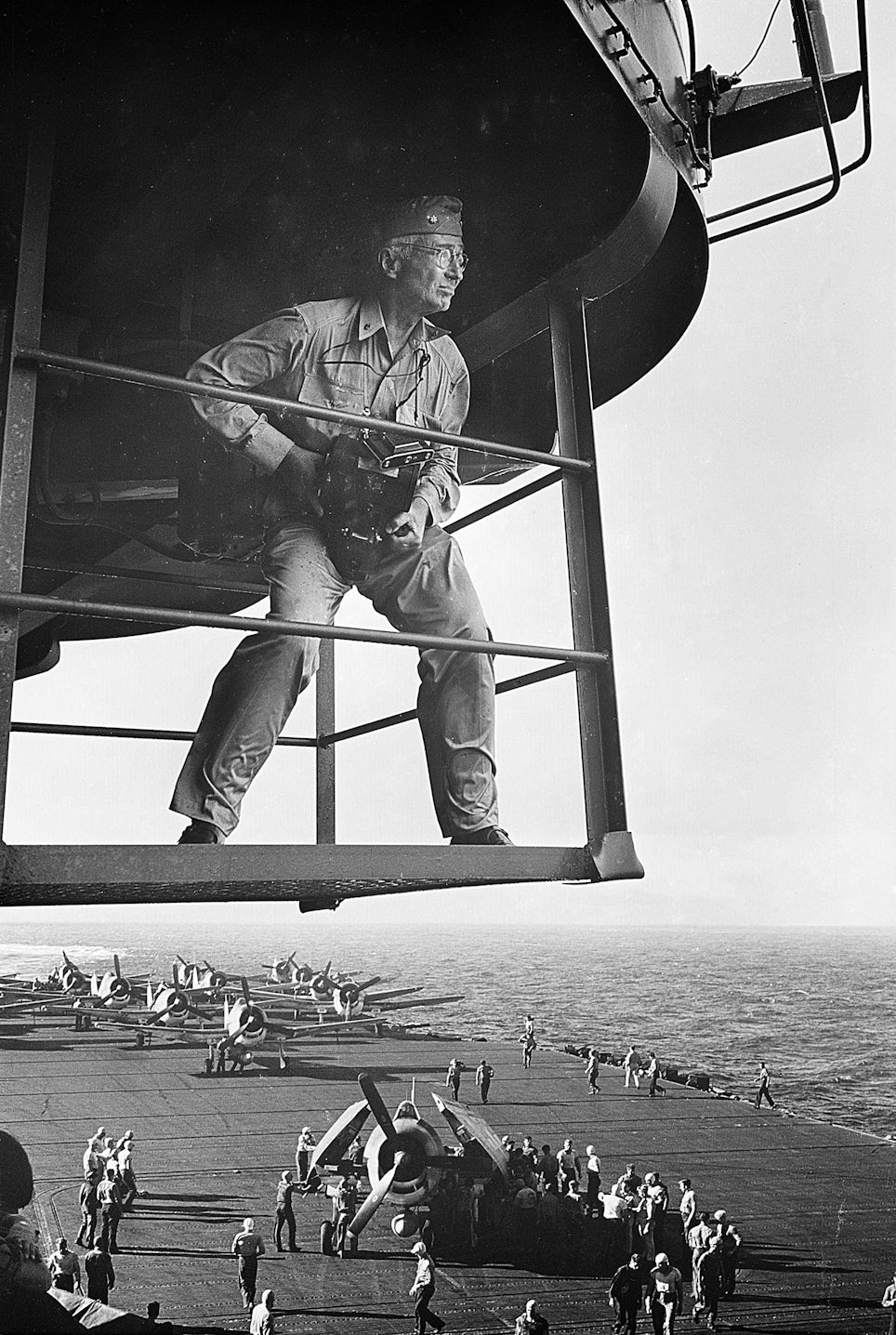

Victor Jorgensen, Commander Aboard USS Lexington. Commander Edward Steichen stands on a platform overlooking the deck of the USS Lexington. Propellor airplanes are on the deck, 1943 © CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

During World War II, as he was 62, he joined the US Army to serve as Director of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit. He thus contributed to establish an ideological and aesthetic image of the war from the American point of view. This conflict would leave him a persistent painful impression. He developed a deep hatred for war which strengthened his convictions that photography had a part to play so that such a tragedy would never happen again.

1947-1973: Consecration, nomination at MoMA and a lifetime achievement

When he was named the director of the Photography Department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from 1947 to 1962, Steichen’s photographer career became secondary and he dedicated his time to make other artists famous.

He organised 44 exhibitions in 15 years and published his autobiography A Life in Photography, the story about a man whose life and art concept were merging. In 1951 during the Cold War, he realised his third exhibition at the MoMA Korea – The Impact of War – which didn’t meet the success he had been expecting.

Steichen then turned towards something he had long been maturing. He began preparing his project The Family of Man. Travelling through Europe and the United States he collected the photographs that would compose his exhibition. It opened at MoMA in 1955, then toured the world until 1965 as a consecration of his most ambitious project: to explore the potential of photography as a means of communication and prove its capacity to interact with the world as much as it was showing it.

Ezra Stoller, Entrance of the exhibition "The Family of Man" at the MOMA, 1955 © Esto

Photographer Edward Steichen (standing, center), director of photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art, assembles some of the photographs to be included in the Family of Man exhibition at the museum, New York, January 25, 1955 © Getty Images

When I first became interested in photography, I thought it was the whole cheese. My idea was to have it recognized as one of the fine arts. Today I don’t give a hoot in hell about it. The mission of photography is to explain man to man and each man to himself. And that is no mean function.

Edward Steichen

The exhibition was gathering 503 photographs by 273 amateur and professional photographers from 68 countries. It was shown in nearly 160 museums and welcomed about 10 million visitors in 10 years.

In 1957 his second wife’s death after 34 years of marriage left Steichen devastated. And yet in 1960 he remarried Joanna Taub -54 years his junior. In 1961 he realised his last exhibition under the simple title Steichen the Photographer. When he retired, he was named Director Emeritus of the MoMA and was responsible for selecting the photographs that would build up his last exhibition as a curator The Bitter Years. In 1964 the Edward Steichen Photography Centre opened at the MoMA.

Edward Steichen died on March 25th, two days before his 94th birthday. What he left as a legacy to photography and what he taught about, its worldwide scope will never cease to inspire the future generations of photographers and its print will always persist in Luxembourg.

Steichen heritage in Luxembourg

Steichen’s work is omnipresent in Luxembourg. The National Museum of History and Art (MNHA) holds a collection of his personal and artistic work that gives a comprehensive overview of his art. It is shown in cycles in a gallery entirely dedicated to the photographer. These exhibitions also propose photographs collected by the City of Luxembourg. In the Gallery Am Tunnel of the Banque et Caisse d’Epargne de l’Etat (BCEE), a selection of his works is permanently shown. At last, two of the exhibitions he had created for the MoMA as curator for the New York museum are held at the National Centre for Audiovisual Arts (CNA); The Family of Man is displayed at Clervaux Castle and his last exhibition realised in 1962 The Bitter Years is carefully preserved in the archives of the CNA.

Howard Sochurek, Photographer Edward J. Steichen © The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images